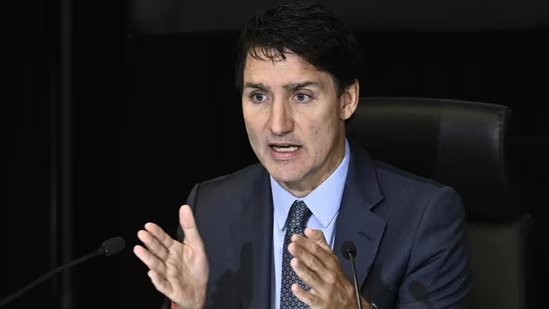

Justin Trudeau is killing Canada’s liberal dream

“It is A time of massive anxiety.” Justin Trudeau was talking about Canadians’ economic outlook, pitching the durability of his liberal project to a gathering of global progressives in Montreal last month. “People notice the hike in their mortgages much more than they notice the savings in their child care,” he offered, perhaps implying that in doing so people failed to appreciate all he did for them.

A diagnosis of anxiety fits his own government, too. Mr Trudeau and his party have traversed an arc from heroic to hapless during nine years in office, and today are despised by many in Canada. Polls suggest that less than a quarter of the electorate plans to vote for him. With under a year to go until a general election, Liberal Party members fear no plan exists to increase that share. They have lost two by-elections in quick succession, as well as the support of their governing partner, the New Democratic Party. A letter has been circulating among Liberal MPs calling upon Mr Trudeau to resign. Massive anxiety indeed.

Mr Trudeau became a beacon of morality after he swept to power in 2015, welcoming refugees to Canada from war-torn Syria that Christmas. He legalised marijuana, rewarding the record number of young people who had voted for him. He faced down a truculent President Donald Trump to salvage the North American trade pact that is foundational to Canadian prosperity. His government’s annual payment to families of up to C$7,787 ($5,660) per child under six is hailed for lifting 435,000 children out of poverty. After promising child-care subsidies to help more women to work, working-class and younger voters gave him renewed minority mandates in 2019 and 2021.

Three years later those groups have turned on Mr Trudeau. Today both tend to support the opposition, Pierre Poilievre’s Conservatives. What went wrong?

The unaffordability of housing is central. The cost of owning a home in Canada has increased by 66% since Mr Trudeau took office, with prices rising faster in this century than in any other sizeable OECD country bar Australia. Lack of supply is a problem in many but is especially acute in Canada. In 2022 the average OECD country had 468 dwellings per 1,000 inhabitants. Canada had 426, a number that has hardly moved in a decade (see chart 1). Mike Moffatt, a housing economist, says a “wartime effort” is needed to triple the current building rate and throw up 5.8m houses in the next ten years. No such luck. In August Canadian housing starts dropped to an annualised rate of 217,000.

The influx of immigrants during Mr Trudeau’s decade in power has intensified the demand for housing. The number of temporary foreign workers jumped from 109,000 in 2018 to just under 240,000 in 2023. The number of non-permanent residents—including temporary foreign workers, students and asylum-seekers—has more than doubled from 1.3m in 2021 to over 3m on July 1st, according to Statistics Canada, representing 7.3% of Canada’s total population of 41m.

The education and healthcare systems have also felt the pinch. Universities are bursting with foreign students, often lured by unscrupulous overseas middlemen offering “sham” degrees, according to Mr Trudeau’s immigration minister, Marc Miller. Some 560,000 student visas were handed out in Canada last year. Mr Miller is cutting that number to 364,000. “It’s a bit of a mess, and it’s time to rein it in,” he said earlier this year. Some elementary school teachers flounder, as they grapple with the children of recent arrivals who often speak neither of Canada’s official languages, English and French.

The pain of high housing costs has been compounded by a mediocre economy. Canada suffers from laggardly productivity growth, which has suppressed wages. Investment has been strong in oil- and gas fields, and in extractive industries more generally, but has been overshadowed by other parts of the economy. The share of tech, R&D and education, taken together, in total investment is lower in Canada than anywhere else in the G7 club of rich countries.

Canada’s economic ties with the United States have created problems since the end of the pandemic. American spending switched disproportionately to domestic services after lockdowns ended. This left Canadian manufacturers—whose goods had been flying off the shelves to online shoppers south of the border—in the lurch. The Canadian services sector had to pick up the slack, relying on Canadian demand to drive growth in the economy.

Higher interest rates made that a tall order. In Canada, where most mortgages are sold with rates that are fixed for five years, rate increases hit consumer spending power harder than they did in the United States, where fixes usually last for 30 years. Canadian households were already dealing with more debt, relative to income, than any other G7 country. On average 15% of disposable income is now spent on servicing debt, an increase of 1.5 percentage points since 2021. Americans spend 11%. Canada’s government has not been splurging to try and ease the pain. It ran a budget deficit of 1.1% of GDP in 2023, the lowest of any G7 country (see chart 2).

Climate change offered Mr Trudeau perhaps his clearest opportunity to blend moral leadership with pragmatism. But he ignored polling showing that while Canadians were concerned about the climate crisis, they were also loth to pay taxes equivalent to a Netflix subscription to fight it. His carbon tax, introduced in 2019, imposed a levy on greenhouse gas emissions. It currently runs at C$80 per tonne, scheduled to rise by C$15 annually to reach C$170 per tonne in 2030. Canada’s parliamentary budget watchdog said on October 10th that most households would be worse off when indirect costs of the tax were factored in. Mr Trudeau’s failure to find a way to compensate groups who lost out as a result of the tax left it and him vulnerable to criticism from Mr Poilievre; he says the tax will lead to “nuclear winter”, trigger “mass hunger and malnutrition” and compel poor, older people to freeze. Support for the carbon levy has crumbled.

Mr Trudeau’s standing is not helped by the waning under his Liberal government of Canada’s influence in global affairs. When it last tried to win a seat on the United Nations Security Council in 2020, it finished behind Norway and Ireland. It spends just 1.3% of its GDP on defence, far below the 2% required of NATO members, and the pace set by rearming European members facing an expansionist Russia (see chart 3). Mr Trudeau has promised Canada will hit the 2% level in 2032. Meanwhile, relations with Asia’s most populous countries, China and India, remain ice-bound. On October 14th India and Canada each expelled the other’s high commissioner, the latest move in an ongoing spat between the countries over the murder of a Sikh separatist in British Columbia last year. In the Middle East, Israel’s prime minister, Binyamin Netanyahu, does not return Mr Trudeau’s calls.

Instead of adapting to or confronting challenges thrown up by his policies, Mr Trudeau has preferred to attack his critics. He has seemed inert as the erosion of his party’s support accelerated. Some Liberals privately suggest the breakdown of his marriage last year distracted him. In a shuffle aimed at energising his front bench in 2023 more than half his cabinet changed portfolios, but the economic message remained the same: we will continue to deliver “good things” to Canadians. Only recently has Mr Trudeau begun to acknowledge that this fell short. “Doing good things isn’t enough to deal with the kind of anxiety that is out there,” he told the Montreal conference. He still describes his voters’ problems in psychological rather than practical terms.

Boxed out

Mr Poilievre identified that economic anxiety early. This lent him credibility with the sectors of the Canadian electorate who felt abandoned. He has boiled his platform down to a series of simple three-word slogans. He says his first piece of legislation will be to “axe the tax”, ditching the carbon levy. He has yet to outline what actions his government would take to fight climate change, but polls make it clear that Canadians care far less than they used to. All too many have forsaken Mr Trudeau and the causes he stood for.

Editor’s note (October 15th 2024): This story has been updated with news of the tit-for-tat diplomatic expulsions from India and Canada.

Correction (October 16th 2024): An earlier version of this article cited a figure of C$50 per tonne as the current level of Canada’s carbon levy. In fact, it is currently C$80 per tonne. Sorry.

Disclaimer: The copyright of this article belongs to the original author. Reposting this article is solely for the purpose of information dissemination and does not constitute any investment advice. If there is any infringement, please contact us immediately. We will make corrections or deletions as necessary. Thank you.

Title:Justin Trudeau is killing Canada’s liberal dream

Url:https://www.investsfocus.com